Ethics today means not being at home in one’s house.

-Theodor Adorno

Climate change is about the future infiltrating the present. Our ethics don’t stretch to universals, to global threats, to timelines beyond our lifetimes. Monsanto House of the Future is a project that addresses climate change after the future, to borrow Franco “Bifo” Berardi’s term that was a significant reference point for this project. Climate change as both an inevitability and as a globally-inscribed condition is just one inroad of many that lead us to a view of the future predicated on collapse. The narrative, the documentable reasons, are insignificant when seen from a post-futurist landscape. We are only left with the results – a landscape we are unable to imagine, inhabited by forms of life we can’t yet recognize.

This project follows an arc of four ‘houses’ that speak to our own revised futures, renegotiated in relation to the architecture of a changing landscape. In 1957, Monsanto unveiled its faux-Mondernist “House of the Future” at Disneyland, showcasing a home meant to advertise advances in “the first truly manmade material: Plastics.” The structure was on view for only a decade, renovated twice in its short run to keep up with evolving views of the future, before apocryphally being dismantled with hacksaws, claws and torches after the wrecking balls bounced off its plastic skin. After demolition, its base was left, eventually becoming an alpine forest, then a fountain, fairy land and souvenir stand before finally being used as a monumental-scale planter – its form upturned, soiled and seeded. The House of the Future spoke to a particular moment that has eroded in subsequent decades, in part due to Monsanto’s own environmental legacy.

A second ‘house of the future’ is the Svalbard Seed Vault, a ‘doomsday’ seed bank containing hundreds of thousands of seeds from around the world collected in a secure, climate controlled vault in an effort to preserve biological diversity in the face of ecological collapse. The vault, located on the edge of the Arctic, is wedged in a mountain and then even more deeply frozen so that it would maintain its temperature for twenty years after a complete power failure in the face of even the most dramatic predictions of global warming. This is architecture in survivalist mode, whose mute text speaks of the brink we each expect. Rising temperatures, rising tides; loss of genetic diversity and GMO’s; human-caused, anthropogenic events such as nuclear war, bioterrorism, or other global crises are internalized. Our anxieties are the subtext of our times, explosively expanding outward, shaping this post-collapse house kept on ice.

Third, we return to a subsurface fire at a Bridgeton Landfill, a complex collision of chemicals that is edging towards a site with illegally-dumped radioactive waste that will burn for generations beyond us. The site, whose form is reminiscent of the nearby burial mounds at such sites as Cahokia, contains a ‘seed’ that will continue growing for generations beyond our ability to keep seasons and parse time. This neighboring house records a narrative of our time that we can’t live in, but may be buried in. It speaks of a complex society reduced to earthforms, to archeology. A non-parable, the landfill is an image of damage stretching out generations. We can’t process the knowledge, it shivers through us and disappears, a news cycle that mirrors our own incapacities to dwell on an unfurling future we are afraid of — some unseen, but observed fire sprawling out under us, beyond us, because of us.

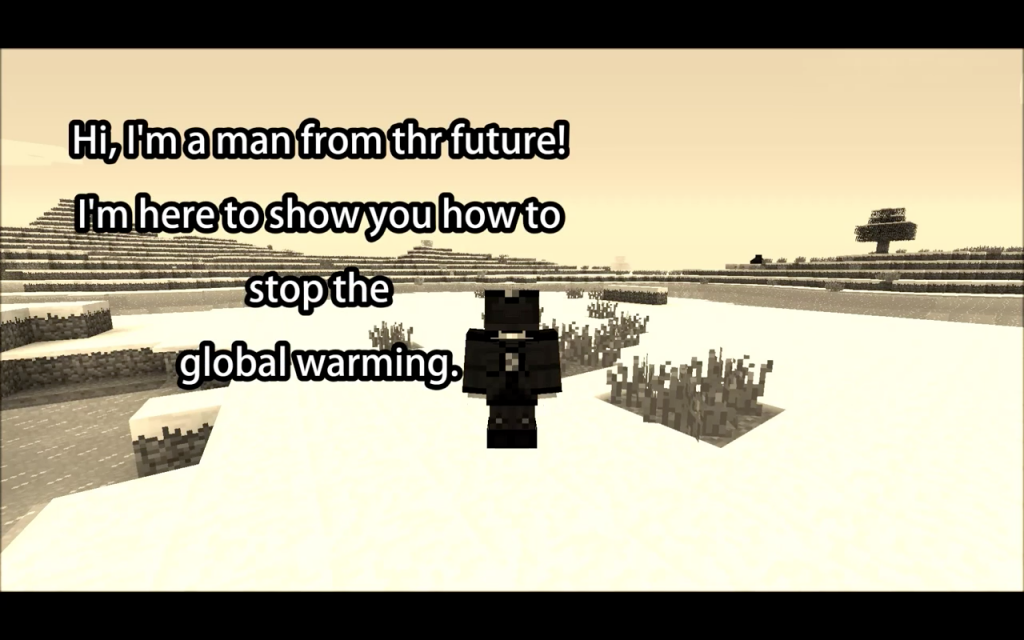

Finally, our house merges with the speculative – the mods of Minecraft or Marvel, where we play out our fears, succumb sometimes, conquer sometimes. This is the house we live in, the home we flee to, where we can displace our uncertainty into a rhythmic ritual of building, rebuilding, casually creating a wasteland and replanting it the next day. We zoom in and out of the future, we toggle our options. It allows us to accumulate knowledge, yet act without it. Our chaos is entertained; screened and rescreened. We are in the fog of our unknown futures. The chaos cascades forward – we have experience from our ancestors, yes – and we must manage the knowledge without knowing, really, anything.

As Theodor Adorno wrote in Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life, “ethics today means not being at home in one’s house.” Our concern is in how to be absent from these houses, to carry our home with us, wandering. Viewing our time after the future, we attempt to see what persists pasts us when our narratives stretch out and intersect with a landscape that survives us. Perhaps in this vision, we see staggered steps that helps us build other houses we may live in. The question is how we can even speak of it – how we can imagine an ethics after the future that allows us to address ourselves in the present.

For Marfa Dialogues: St. Louis, on July 30th at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, US English will present Monsanto House of the Future, a new performative lecture consisting of a video, voiceover, and live score by The Rats & People Motion Picture Orchestra and a publication that considers climate change as seen through speculative architecture and our changing views of the future.

US English is the collaborative project of Brea and James McAnally, exploring collective identity, spatial politics, and forms of protest through a diverse collection of text, sound, objects and interventions, often initiating large-scale projects in public space. US English acts as both a pseudonym and a form of speaking — an acentered voice in a society of words.